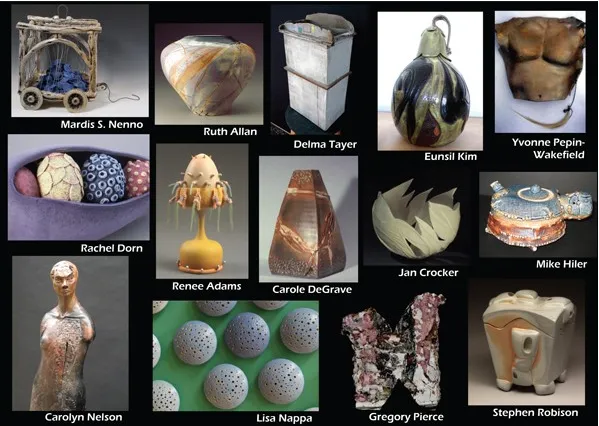

“When people think of something made of clay, they immediately think ‘vessel,’” she says. “This show goes far beyond that. Many of the pieces are more like sculpture than the traditional notion of the clay vessel. I’m trying to get away from the idea that clay is always a dish.”

A piece like Ellensburg artist Renee Adams’ “Crowned Polylyp,” for instance, is definitely not a dish. It’s not really any one thing at all. It evokes sea life or plant life or some kind of alien life.

“She’s transforming this idea of nature into crafting it into almost a surreal vision,” Hahn says. “You wonder, did it come from the ocean? Did it come from a body? Is it growing from the earth? That’s the mystery of it. I find that very fun and intellectually inviting.”

Then there is “Interior Rhythm,” the human figure sculpted by Carolyn Nelson of Yakima. The piece is very definitely a woman, but it’s not simple. The woman seems to be cracked and crumbling in places, and her entire left torso is composed of bricklike stonework. It is, Nelson says, a notion of humanity heavily influenced by the basalt columns in the local landscape.

“The pieces are very personal,” she says, referring to “Interior Rhythm” and the other two pieces she has in the show. “A lot of my own past is about trying to understand connections between ourselves and the earth, ourselves and layers of time. There’s some back and forth in that piece between ourselves and the earth.”

Clay itself, of course, comes from the earth. In a technological age in which so much of art is digitally manipulated or computer-assisted, clay is a return to the elemental, Hahn says.

“That’s what I like about working with clay: There is a hands-on intimacy in making these things,” she says. “The medium comes from the earth.”

Yvonne Pepin-Wakefield, a Port Townsend artist, gathered the clay for her work at the base of cliffs on an inlet near Fort Worden and the Straits of Juan de Fuca. She had to clean the shells and other debris out of it herself. That sort of connection to the medium is a significant influence on her work, she says.

“We all come from the earth,” Pepin-Wakefield says. “And we’re all going back to the earth.”

Her piece “Jason” is a breastplate molded from the torso of a young football player. The finished clay was layered in oil paint and metallic coating for a piece that evokes strength and vitality. It was a departure for Pepin-Wakefield, who previously had cast only women.

“I wanted to honor the physical form of youth,” she says.

That’s quite different from the spare, industrial looking piece done by Yakima’s Delma Tayer. And it’s different from the elegant vessel created by Yakima’s Carole DeGrave or the out-of-this-world creation Adams has in this show. It’s even different from the human form sculpted by Nelson. That’s the versatility of clay, Hahn says.

“Variety is definitely the theme,” she says. “Some of the pieces are quite whimsical. Others simply sing in the beauty of their form.”

In addition to the exhibit proper, “From the Ground Up” includes a free panel discussion and artist-led slide presentation from 1 to 4 p.m. March 10 and a demonstration by artists Eunsil Kim and Mike Hiler on March 31. There will also be a bus tour to Seattle and Bellevue for the National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts conference in Seattle. Details of that are still being worked out, Hahn said. Those interested can call the gallery, 509-574-4875, later this month for prices and schedules.